Art

Madsen (1904 – 2000) one of Quetico Provincial Park's

original 16 rangers and a sworn officer of the law, helped lay the

foundation of Quetico's vast 1,000,000 acre/600 lake park. Art

patrolled various beats in the Quetico during the

winter—averaging 1500 miles per winter on snowshoes. He

captured two of Quetico's most notorious poachers: one which took Art

three years to track then had to wrestle the armed poacher to the

ground before arresting him. Art Lake lake in the north-eastern section

of Quetico is named in Art's honor. Art lived an adventuresome,

vibrant, long and healthy life. (For more on Art Madsen see Boundary

Waters Journal fall 2000 issue "The

Original Quetico Ranger" or Sagonto.com

“Adventure Articles.”) - (Direct

link to story)

In 1931, Art Madsen

established Sagonto, a wilderness resort on the Canadian side of

Saganaga Lake, bordering the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. In

1946, at the age of 42, he married Virginia “Dinna”

Clayton from Duluth, Minnesota, and most of their

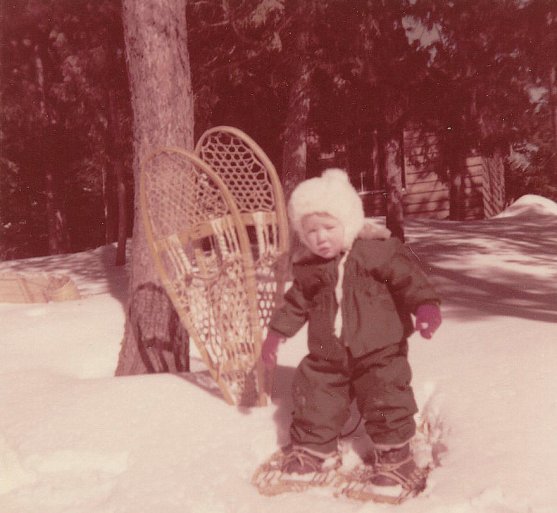

children were born after Art was in his 50's. One of their children, “The

Snowshoe Baby” —dubbed by the media when the epic trek

of Art's expectant wife Dinna and the birth of their daughter received

international acclaim.

By January

of 1956, Art and Dinna had three children aged six, five and two. Dinna

was expecting their fourth child in approximately a week, Art decided

Dinna needed to get “out” to

the nearest hospital, which was in Duluth, where Dinna could stay with

friends or relatives.

Back in 1956, the only means of

communication they received was by mail delivery once a week, picked up

five miles down the lake by another family on the lake using a dog

team. Dinna stated, “In those days the only valid

reason for a woman to leave the lake in the winter was if she had an

abscess tooth or was ready to give birth.”

The first leg of

the 180-mile trek to the hospital in Duluth would be to travel five

miles over the frozen lake to The Gunflint Trail in cold January

temperatures. From there she planned to meet the weekly

mail delivery and get a ride “out”

with the mail truck

66 miles away to the closest village of Grand Marais. If anyone needed

to “go out,” the mail carrier,

Don Brazell, was more than happy to accommodate any of his friends from

Sag, as advance communication to schedule a ride was nearly impossible.

In addition, the neighbors on this remote lake were ready and willing

to help one another at a moment's notice. Once in Grand Marais, Dinna

had planned to travel by bus to Duluth.

This would be an arduous trek under normal winter conditions, but that

frigid January of 1956 with temperatures below zero, the area had a

reported snow level of some 100 inches. The weight from the heavy

snowfall caused the ice beneath to crack and water seeped onto the lake

saturating the snow and creating deep, soggy and heavy slush. Freezing

slush became a torturous obstacle for man, machines and

dog teams. The trip five miles down the lake

would be strenuous for any conditioned northerner, but for an expectant

mother, it would not only be laborious, but could endanger both the

mother and her unborn baby.

Dinna related, “In the winter time the very

small cabin felt even more comforting than usual, especially as I was

large with child number four, and not wanting to go 'out' to the

hospital or to town. But Art was determined to get me 'out'.”

It was decided that Dinna would take their oldest

child, six year old Chris, with her to Duluth. The other children,

Sandy age five, and Chucky age two, were placed in the care of neighbor

Charlotte Powell, who lived six miles north of the Madsen's. They had

gotten word to Charlotte to arrange for her to take care of Sandy and

Chucky while Art transported Dinna and Chris to the landing.

The previous day, Art had

spoken with his neighbor Jock Richardson who lived a half mile away on

the same island, to ask how the Model A (half track) was working. Art

had hoped to use it to transport Dinna and Chris down the lake to meet

the mail truck. Jock said as far as he knew it had been running good. (The

half track was a winterized mode of transportation that Art and Jock

built from a Model A Ford. Art related: “It

had a double reduction gear in the lower end, so you could put a steel

track on it. I kept that thing running for years—we even

hauled logs with it. But with that double traction, the only thing that

would buck it, was if you ran into slush on the lake and it was

freezing hard—then the track would ice up, and the track

would get so tight it would snap.”)

Snowshoeing, Art started

out ahead of Dinna and Chris to travel over to Jock's to prepare the

half track for the trip down the lake. There was slush in front of Art

and Dinna's front shore, and they didn't want to chance the half track

getting bogged down in the deep slush. So, they decided to start out

from Jock's. Dinna said goodbye to Sandy and Chucky leaving them safely

in the care of her close friend Charlotte. Then she and Chris fastened

on their snowshoes and traveled the half mile to Jock's around the

shore.

Art

related, “When I went over to Jock's to get the

half track the next morning, I found out it wasn't working. I

discovered that a condenser had gone out on the ignition, and it took

me a little while to come up with [a replacement] ignition.”

But “the

rush was on,” for Dinna only had so much time to

get down the lake to meet the mail truck, as Don Brazell would not be

back until next week—near her due date!

Art recounted,

“In the meantime, there was a fellow on Sag with one of those

propeller-driven snow rigs with skis on, that we call a

snowboat—similar to what they use in Florida in the

Everglades. He offered to take us down the lake, but he said he could

only go as far as the winter portage, as it was a little crooked on the

portage, and it was hard for him to steer it in there. Also, the

snowboat used aircraft fuel for the engine, and he was short on fuel.

So, he took Dinna and Chris as far as the winter

portage, and I would follow to take them the rest of the way as soon as

I had the half track repaired.”

Dinna stated, “I

bundled up Chris, and I was wearing everything I could, as it would be

even colder riding on that snowboat. We'd have to wait at the winter

portage for Art, but we'd get three miles, anyway. So, Chris and I rode

with Vern Grover, who was from Duluth, to the winter portage. The seat

in the snowboat was a wide plank that stretched about five feet across

the boat. But the ice, slush and snow drifts had frozen

into rough and jagged shards, and the air boat went very fast causing a

sharp jar with every bump we hit. At one bump, we came down so hard

that the plank seat cracked—it didn't quite break through,

and eventually we did end up on the winter portage and gladly piled

out.”

Dinna continued: “It

was bitterly cold, and we were still two miles from the end of the

road—the top of The Gunflint Trail. I had a hungry six year

old to entertain—Chris was getting antsy about

waiting.”

Dinna told him that she was going to start a fire to help them keep

warm. Chris related to his mother how he had read that “the

Boy Scouts could start a fire with just one match,” and

challenged her if she could do the same. “I had to

to prove that his very pregnant mom could do no less. The portage had

birch trees and lots of dry tree branches, and I also found an old, dry

stump that had dry chaff in the hollow middle. So, it was no time at

all that the fire was blazing away with rocks to corral the fire. The

fire cheered him quite a bit, but by then we were both

hungry.” Dinna recalled.”

Art soon had the faulty

condenser fixed—even in spite of working in the freezing cold

with his bare hands. So, he started out to meet his wife and son, but

quickly ran into slush! The area had nearly two feet of snowfall the

night before, causing the lake to become very slushy. Even for the most

experienced winter traveler, slush is often impossible to avoid. In the

frigid temperatures, it quickly froze to the tracks and snapped them.

Art had seen Irv Benson go by with his dog team and knew that Irv, upon

seeing Dinna and Chris on the winter portage, would offer them a ride.

But, Art had Dinna's suitcases with him, and he needed to get them to

her before the mail truck arrived. He would have to leave the half

track and take care of it later that day. Art had his handmade-wooden

toboggan loaded on the back of the half track along with his snowshoes.

He unloaded the toboggan and his snowshoes, leaving Dinna and Chris'

snowshoes in the half track, as he was certain they would have gotten a

ride with Irv and would be at the mail-truck stop by now.

Strapping on his Michigan style snowshoes, he

began the strenuous journey of slogging down the lake through the

weighty slush. The slush was some of the worst he had seen, and it was

as if he were lifting 20 pounds of lead with the heavy slush that froze

instantly to his snowshoes with every step. Art carried a stick and had

to continuously hit the sides of his snowshoes to dislodge the freezing

slush.

Dinna, waiting at

the winter portage, recalled: “Suddenly, we could

hear someone coming with a dog team! It was our neighbor Irv Benson

(who lived on the island behind us) with his team and sled. Irv had a

load of furs to send out with the mail truck, and he informed us that

the slush was very bad. Irv offered us a ride, but his sled had quite a

load on it with his furs. At the same time, Art had just started out

with the half track three miles away. I could faintly hear the half

track's engine, off and on, as the wind would pick up the rumble and

carry it around the islands and trees. I was confident that Art would

be coming soon on the half track, so I declined Irv's offer. Irv then

left with his dog team to catch the mail truck. Chris and I continued

to wait.

Little did we

know that the half track had thrown a track and was bogged down in

heavy slush.”

When Art reached the winter portage, he was alarmed

and quite distraught to find his pregnant wife and young son still out

in the freezing temperatures. If Dinna had gone into labor, she would

have been without any help—he was understandably concerned.

Art only had

his snowshoes and it was such “tough

going” that he knew it would be nearly impossible

for Dinna to struggle through the thick slush the remaining two miles.

Art, certain that Irv would have stopped and offered Dinna a ride,

asked her why she had not gone with Irv and his dog team. Dinna

replied, “Because I heard the half track running and

knew you would be here shortly.”

“Art had a small toboggan with our suitcases,

but not our snowshoes. So, he tied his snowshoes onto me. In that deep

slush I could only walk fifteen steps, then I had to rest and then

start again. Our legs were so tired, and Art had to struggle along

himself without any snowshoes, assist Chris and tow the toboggan as

well. Art was plodding in the snow up to his knees, and Chris was

following in Art's footsteps, and whining as he was sinking almost the

entire length of his little, six year old legs.” recounted

Dinna.

“ The

baby kept moving, and Art was afraid that we were going to have it

right there. I did my best to stay calm and focused by telling myself,

'Take it easy, but push onward. Hurry up, but go slow.”

They continued on, making slow progress, but somehow managed to

complete two miles. Upon rounding the bend to the last stretch of ice,

snow and slush, the landing was in sight. Irv Benson saw them heading

his way, struggling through the deep snow and slush. Seeing their

predicament, he hitched up his dogs again and came to meet them to

transport them the last one-half mile for some reprieve. The mail truck

still had not arrived; and for some unknown reason, it was way behind

schedule.

Art said good-bye

to Dinna and Chris at this point to return to the island and kids. He

quipped, “All I had to do was snowshoe the five

miles back home through that heavy slush!”

Dinna

said, “Chris and I rode on Irv's dog sled to the mail truck

stop. We greeted George Plummer and Charlie Cook. They were from

Gunflint Lake, and were also waiting for the mail truck to arrive. We

all stood waiting for the mail truck, but it was getting colder all the

time, and there was no sign of it coming! And no place to sit and rest.

After some time, George said they were going to drive over to Russell

and Eve Blankenburg's on Seagull Lake to use the

phone to find out what had happened to the mail truck. When George

arrived at Blankenburg's, Eve told him that she had

already called and the mail truck would not be making it up The Trail

that day for there had been a 17” snowfall on The Gunflint

Trail. Neither the mail truck nor the snowplow made it up The Trail

that day. When George informed her that I had come down

the lake to get out to Duluth, Eve invited me to spend the night at

their place. So, George came back to take Chris and me to

Blankenburg's,” said Dinna.

Dinna continued, ”Somehow, George was able to get his car

through those rough and icy, dirt roads to Blankenburg's on Seagull. It

had been a long day. We had started out at 8:00 a.m., and it was nearly

5:00 p.m. when we arrived at Blankenburg's cabin. Eve greeted us warmly

and had dinner ready for us. We spent the night in a little 8 x 10

cabin, while Eve and Russell stayed at a cabin nearby. There was a

small, wood heater in our cabin, and Russell had the fire going to thaw

out the cabin for us. I was still chilled, and that

evening in an effort to warm up, I must have had a dozen quilts on me.

But, each time the fire went out, it cooled off so quickly, I found my

boots frozen to the floor!”

In case Dinna needed help during the night, Eve gave her a cow bell to

ring to signal for assistance. There was a blasting wind

that night, and Dinna did not need to ring the cow bell during the

night, but needed to ring the bell the next morning, as Dinna could not

open the door of the cabin. There was a snowdrift blocking the door on

the outside due to the blizzard during the night—and the door

was frozen shut.

“As soon as I rang

the bell, Eve came over on the double and got the door open,”

Dinna stated. “Then Eve shoveled the trail over to

their cabin before we went over for breakfast. The trail had drifted

over about three feet deep.”

Eve called the county snowplow custodian to inquire when the snowplow

would clear The Gunflint Trail that day. The road had already been

closed for many miles the previous day. The custodian informed her that

it may be two to three days before they could plow The Gunflint Trail.

Dinna said that Eve was a little nervous, and didn't

want a maternity case on her hands, so Eve told the man, “My

husband is one of the biggest taxpayers in the county, and we've got an

expectant mother here, and we want to see that snowplow,

today.”

When the snowplow finally made

it to the end of The Gunflint Trail that day, Russell and Eve drove

Dinna and Chris to Grand Marais following the snowplow on its return

trip. They stopped in at Leng's Soda Shop (the hub in Grand

Marais at the time) for Russell to use the phone.

Russell called Ade

Toftey, the publisher/editor of the Grand Marais Cook

County News-Herald and Eve related the story of

Dinna's trek thus far. Ade Toftey jotted down the information and then

sat down and wrote an article about Dinna's strenuous journey down the

lake by foot, snowshoe, snowboat, and dog team—then to Grand

Marais and Duluth by car and bus, in order to get

“out” and make her way to the hospital to deliver

her fourth child.

The next morning, Dinna and Chris caught the

Greyhound to Duluth. At the same time, Ade Toftey's article went out

over the Associated Press wires, and newspapers from all over the

country picked up the story. As soon as Ade's article

hit the papers, it began to create a public stir. Readers from numerous

states wrote to the papers to ask if the baby had been born. Also,

hospitals in St. Paul, and Minneapolis, wanting to help, offered for

Dinna to have her baby in the Twin Cities. Two gynecologists from

Illinois, who spent fishing vacations at the wilderness resort earlier

that year, invited Dinna to come and have her baby in Illinois, gratis.

News releases and radio programs discussed which city Dinna should

chose for the delivery of her baby.

But, Dinna, not wanting to travel any farther, decided to stay with

friends in Duluth. The next edition quoted Dinna, “It's

much better for me to stay here. Besides, it would not really be wise

for me to keep on traveling.”

As the newspapers continued

publishing stories and photos about Dinna and her six year old son

Chris—covering his introduction and reaction to city life,

his first experience attending a school classroom,

etc.—public interest grew. In a letter Dinna had written to

Art at the time, described, “Chris says 'Hi' to

everyone he meets!” Dinna enrolled Chris in Bay View

School's first grade: “Wilderness

Mom's Son Spends 1st Day in School” It

was reported: “Dinna

had been tutoring her son at home (using Canadian correspondence

lessons) and forwarding his work and tests to school officials in

Toronto. Although he is 'up on his lessons,' he had never been inside a

schoolhouse.”

Then Dinna's delivery day

arrived! On February 6th, Dinna gave birth to a

girl, Helen Sue. The only way that Dinna could notify Art of the birth

of their new daughter was the interruption of a radio program of which

he would be monitoring every morning at 7:00 a.m. Dinna contacted KDAL

in Duluth, and the message was delivered

over the Eddy William's Program

(a country music program that played callers' requests).

Art was listening in his cabin on Saganaga,

and heard the announcement over the radio that all was fine, and Dinna

had given birth to a baby girl!

Dinna had now

become known as the “Mushing Mother of the

North,” and at the birth of her

daughter Helen Sue, Jim Klobuchar of

the Minneapolis Star Tribune

sent the story (which had been mounting in the press) and the

announcement of the birth of Dinna's daughter, over the International

Press wires. Helen Sue was dubbed forever after as “The

Snowshoe Baby.”

Art and Dinna received mail

from around the globe congratulating them on the birth of their

daughter and asking many questions about their wilderness life.

Numerous articles with variations on the trek were sent to Art and

Dinna with titles such as: “By Dog Team,

Snowshoes: Expectant Mom Mushes Way to Village”;

“Baby's Birth Near, Mother Treks

Across Wilderness to Doctor”; “Everything

From Snowshoes to Bus 'Outruns' Stork.”

The mayors of

Grand Marais and Duluth presented Dinna and her new-born baby with a

number of gifts, some of which were winter toys for the older siblings

and hand made, baby snowshoes for Helen

Sue. Dinna

was given credit for “putting Grand

Marais on the map.”

Art had written to Dinna on February 12th,

1956, planning the details of her return to the lake:

“Dear Dinna, Chris, Frank and Emma,

Here I am again after reading all your mail. I

went down with Jock and the snowmobile yesterday, the piston came for

[the] snowboat. So I'm going over to put it in this morning. Then I'm

running Jock down as he is leaving today. I started up his truck down

there yesterday, hard to start after sitting so long. I'll be hauling

the mail while Jock is away, so I'll be there Saturday mail time 1:30.

I'm sure Don would bring you up from Grand Marais if you phoned him...

Charlotte will be at Jock's. So if [you are] coming sooner than

Saturday [the] 18th, phone Superior Airways [in]

Fort William [now Thunder Bay], so I can meet you. I'm glad you had a

local doctor...

Well, I've got to get along and fix that engine. Oh,

yes, the kids get a bath once a week whether they need it or not. So

long for now, and will be seeing you, I hope.

Art, Sandy,

Chucky

P.S. Got

snowboat going. Caught trout and two northern—why not come

up, Frank, over Sunday?” [Dinna had been staying with friends

Frank and Emma Lighthizer before and after the birth of her daughter.]

After much ado from the media and television

interviews, Dinna began her return trip to her

wilderness home and family. Art, using Jock's snowboat, traveled down

the lake with Sandy and Chucky to meet Dinna, Chris and his new

daughter. Reporters had followed to request interviews with Art. Art

stated, “Those news hawks weren't going to get me!” At last, Art transported the family the five miles

over the frozen lake to the refuge of the peace and quiet of their

island home.

In

subsequent years, the Snowshoe Baby story would resurface through the

media from time to time, by way of newspaper, radio and television

coverage, chronicling Helen Sue's life: “Snowshoe

Baby Goes to School”; “Snowshoe

Baby, Born after Trek, to Marry Today” Helen

Sue married Marco “Marc” John Manzo (Purser with

Northwest Airlines) of Tacoma, Washington in February of 1974. The

marriage announcement went over the Associated Press wires and Paul

Harvey also announced it on his radio broadcast.

Then, in

October of 1976: “Snowshoe Baby Has

Baby.” KING 5 TV News

(NBC) of Seattle aired an interview of Marc, Helen Sue and Dinna

covering the October 16th birth of her first

baby. Marco John Manzo III was born in their Sheraton hotel room in

Spokane, Washington.

Ten days before her expected

due date, Marc, Helen Sue, Art, Dinna and other family members, were

staying at the hotel in Spokane. Helen Sue went into labor and they

prepared for the 50 minute flight to Tacoma, where their doctor planned

to meet them at the airport. Her husband called the airport to learn

that fog at SEA/TAC delayed their flight, subsequently their plans were

changed and they remained where they were. It was a short labor and her

husband delivered their son, with the support of Dinna standing by.

Marc immediately communicated with their doctor for any “post

delivery instructions.” But, all was well, and Art

(then 72) joined them soon afterwards to meet his first grandchild!

They flew home the next morning. Later, news articles arose: “Stork

Waits for Snow, But Not For Fog.” Marc

and Helen Sue also have a daughter Alesha Leanne Manzo who was born at

home (as planned, whom Marc also delivered as the midwife

arrived late) in February of 1981.

Several

times throughout the years, Paul Harvey would tell

various stories about Art and Dinna and the Snowshoe Baby account.

Ade Toftey, the

publisher/editor of the Cook County News-Herald

received “The Story of The Month Award”

from the Associated Press. He also received a letter of commendation

from a professor of journalism at UMM who had been using Ade's story of

the Snowshoe Baby in his classes. He said that Ade's story was a

perfect example of one that needs no editing. In 1991, in a tribute to

Ade in the Cook County News-Herald,

the paper stated that throughout his 40-year career, his all-time

favorite story was Mrs. Art Madsen's epic journey.

The “Snowshoe Baby” had a career as a court

reporter and then “retired early” at the age of 27,

to be a full time mother and to educate her children at home, allowing

her family the flexibility to be able to assist Art and Dinna at their

wilderness resort. Consequently, Marco and Alesha have spent almost one

third of their life growing up at Sagonto, and grew very close to their

grandparents.

Later, Helen Sue taught

music theory to children at the University of Puget Sound through the

Community Music Department. Then until the fall of 1999, she taught

private piano lessons to 40 students each week with 40 students on a

waiting list, with her daughter Alesha teaching these students music

theory. In their teens, Alesha and Marco were city and state

representatives in classical piano. Her daughter (24) is also a

registered piano teacher. And her son (28) who has trained in flight,

obtained his instrument rating and multi-engine license.

Each year since Marc and

Helen's marriage, they, and later their children, have assisted Art and

Dinna in operating their wilderness resort. Art died eight days before

he reached 96 years of age in July of 2000. Dinna, now 83, is still at

the resort on Saganaga Lake during the summer months. After the death

of Art, Marco moved to the island to assist his grandmother Dinna full

time—where he is following in his grandfather's footsteps and

has found his home in the wilderness.

“Five

miles across that lake—it's a piece of cake in September. It

wasn't like that in January of 1956. That was an adventure, that's for

sure. But it is never as beautiful as it is in the middle of

winter,” Dinna stated. From time to time, Dinna still has

people stop her in Grand Marais to ask, "Are you the lady who had the

Snowshoe Baby?”