|

"The Original Quetico

Ranger" was published in the fall 2000 issue of the Boundary

Waters Journal magazine.

|

|

|

THE ORIGINAL

QUETICO RANGER

by

Helen Sue Manzo

"When

Art was a ranger, much of

Quetico wasn't even mapped — you had

to be a real bushman."

"Art captured and arrested two of Quetico's

most notorious outlaws. Art [risked] his own

life by wrestling the outlaw free of his rifle.

[One] particular criminal complained,

'Oh, you're going to tie me up like a dog?'

Art replied, 'Be a man and you

won't have to be a dog'."

|

|

The last living of Quetico's original 16 rangers died July 26,

2000-eight days before his 96th birthday. In his eulogy, Jon

Nelson, a former ranger at Cache Bay on Saganaga Lake in the

1970's and '80's, shared of Art Madsen: "There is no comparison

of the duties the original rangers performed and the duties

the rangers perform in modern times. Today the rangers are flown

to their posts, and they have boats and motors and are generally

there just to issue permits. When Art was a ranger, much of

Quetico wasn't even mapped-you had to be a real bushman."

At the time Art ranged, from 1934 to 1940, the Quetico rangers

were sworn officers of the law, and .38 revolvers were issued

to the senior rangers. The duties they performed were similar

to the Mounties.

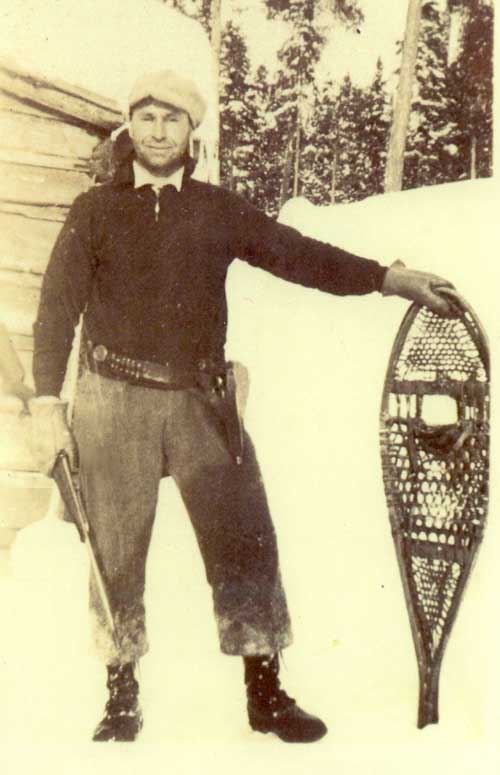

Patrolling by canoe in summer and snowshoe in winter, these

early

rangers canvassed specific routes or "beats" to ensure preservation of the vast game refuge and protection from poachers and outlaws.

Art stated, "I've snowshoed and canoed thousands of miles patrolling, and there isn't a lake in all of Quetico that I haven't been on. I estimated that, in one winter alone, I put on 1,500 miles on snowshoes."

Art captured and arrested two of Quetico's most notorious outlaws. One capture involved Art risking his own life by wrestling the outlaw free of his rifle. Art added, "…while my partner was shaking in his boots." This particular criminal complained, "Oh, you're going to tie me up like a dog?" Art replied, "Be a man and you won't have to be a dog."

|

| |

|

"I've snowshoed and

canoed thousands of miles patrolling, and there isn't a lake

in all of Quetico

that I haven't been on. I estimated that, in one

winter alone, I put on 1,500 miles on snowshoes."

|

| |

|

|

The

rangers were also called upon to dispatch troublesome bears.

Art related, "I've had a couple of close calls with bears.

The last year that I park ranged, the lumber camps were working

off Poohbah Lake. A message came from headquarters that I was

to go down there to take care of a bear." They said, "A

bear is down there getting rough." Art continued, "This

big bear went into one of the drive camps, ripped a board off

the cook shack and reached in and got a ham-it nearly scared

the cook to death. The cook wouldn't stay in the cook shack,

so they all moved into the office. They had moved a lot of the

grub in there too, and the bear tried to go through the window!

Those lumberjacks had to beat him out of the window with their

cant hooks. That's how bold bears can get."

Art spent two nights tracking him with a flashlight and a rifle, but he got him the second night. Upon seeing the tremendous size of the bear, a native Ojibway on the drive said, "Nee-ko-wa muck-wa" (big bear!) The bear was over 600 pounds-the largest Art ever shot.

These original rangers laid the foundation for the Park system, and Art, with his partners, built many ranger cabins on various lakes. Art recounted, "We would have our main cabin, but we had to be on the move every two days to patrol our beat. We had smaller cabins along the beat-generally snowshoeing 20 miles a day to the next cabin. Then we had to travel periodically to report to headquarters on French Lake."

|

| |

|

"I've had a couple of close calls

with bears."

...Art was called upon to dispatch troublsome

bears in the park...

"Those lumberjacks had to beat him

out

of the window with their cant hooks.

That's how bold bears can get."

|

| |

|

The

rangers did their own cooking, including baking their own bread-alternating

days of cooking. Art was well known for his cooking-especially

his raisin pies-and he originated a delicious "Ranger"

soup. When he taught each junior partner how to bake bread,

he would tell them, "Now, I'm just going to show you once,

so watch carefully. We don't have supplies to waste."

Much of the rangers' time was taken up hunting and fishing,

not only for provision for themselves, but to provide meat for

their dogs. While ranging, Art had two dogs to pull a toboggan

laden with supplies, as he would snowshoe ahead to break a trail

for his dogs. He said, "Two dogs can pull you if it's just

yourself without supplies, but otherwise if you want to ride,

you'd better get more dogs. But more dogs, then the more trouble

to feed them."

Art's brother Dick ranged for one season. Art commented, "But,

one season was all he would range, he couldn't take the solitude."

Deep in Quetico's wilderness there were many opportunities to observe unusual activities of wildlife, in particular, the wolves, bear, moose and deer. As a result of this first-hand experience, Art formed a unique perspective on the wolf-refuge controversy, and whenever asked, he offered seasoned advice on maintaining a more balanced wolf/deer ratio.

Born in London, England, in 1904, Art and his family immigrated to Canada when he was about three years old. They traveled to Manitoba by covered wagon pulled by oxen and homesteaded in the Swan River Valley area, where his father also operated various restaurants.

|

| |

|

"He found two men that were adventursome

enough to join him, and thus the three began

the arduous 1,000 mile journey by dog team.

The perils Art encountered on this adventurous

undertaking were numerous."

"He

first entered Saganaga Lake where

he built his home and wilderness

resort September 9, 1931..."

"I

often used to make long canoe trips with

a larger party [sic]. I've gone clean around Hunter's Island,

to Kawnipi Lake, Sturgeon Lake, the Maligne River, Lac La

Croix and around.

That's about 200 miles around there, and oh,

probably 50 to 60 portages."

|

| |

|

|

Art began logging in Manitoba at age 18. At 20, he put himself through mechanic trade schools in Regina, Saskatchewan, and Winnipeg, Manitoba.

He then operated and repaired

steam tractors and thrashers on many farms throughout the region.

His desire was to become a commercial pilot, so in 1929, at

age 25, he organized an expedition to fund his flight training.

His plan was to trap the valuable white fox following the caribou

migration inland near Wollaston Lake, Manitoba. He found two

men who were adventuresome enough to join him, and thus the

three began the arduous 1,000-mile journey by dog team. Art

took two canoes mounted on separate sleds with five dogs pulling

each sled. Will Steger, the arctic explorer who interviewed

Art on several occasions, told how he had made the same trek-but

he made it 40 years after Art's journey, when railroads had

been established along the way which provided points to replenish

supplies. Steger was impressed with Art's expedition,

for in 1929 without railroads

along the route, you literally had

to "live off the land." The perils

Art encountered on this adventurous undertaking were numerous.

On

his return from Wollaston Lake in 1930, he learned of the stock

market crash and was stunned at the economic depression.

Art then came to the Quetico region to work at

a logging camp, where he operated and maintained logging gators on Badwater and Wolseley Lakes, and the Namakan River. Art stated, "They did extensive logging at that time on the western half of Quetico. They used to take out 50 million board feet a year, there. In those days the lumber barons were kings, and no attempt was made to conserve timber for the future."

He first entered Saganaga Lake where he built his home and wilderness resort September 9, 1931, as he and his friend Jock Richardson (a blacksmith from the logging camp) paddled Art's chestnut canoe from Lac La Croix.

In those early years on Saganaga he also guided many parties. Art commented, " Before we got too busy with our own place, why, I often used to make long canoe trips with a larger party [sic]. I've gone clean around Hunter's Island, to Kawnipi Lake, Sturgeon Lake, the Maligne River, Lac La Croix and around. That's about 200 miles around there, and oh, probably 50 to 60 portages-I used to make runs like that."

|

| |

|

"Dinna

snowshoed out to give birth to their

daughter Helen Sue-dubbed by the media as

the 'Snowshoe Baby'."

"Their Native American neighbors taught

Dinna how to build 'tikonnogans'

(baby carriers)...which all of their

children were carried."

|

| |

|

Art was a comrade of the late Ben Ambrose and legend of Ottertrack

Lake. They jointly guided numerous parties, stocked secret lakes

with fish and prospected together. In 1934 there was a gold rush

in the Saganagons Lake area. That same year, Art discovered

and staked the most substantial

find in the region on Cunniah Lake.

Art's last year of ranging was in 1940, as he was conscripted

to work in the aircraft factory at Fort William for four years.

His last assignment at the factory was drafting and producing

the templates for the top and lower hoods of the U.S. Navy Curtis

dive bomber.

After

the war, in 1946, he married Virginia (Dinna) Clayton of Duluth,

Minnesota.

Together they completed building the resort-felling trees for log cabins and, also, turning logs into lumber. The Madsens had six children, with Art in his 50's before most of them were born. Their Native American neighbors taught Dinna how to build "tikonnogans" (baby carriers) made with a back of cedar and a bow (which served as a roll bar) of ash, in which all of their children were carried. In 1956, Art and Dinna made international news when Dinna showshoed out to give birth to their daughter Helen Sue-dubbed by the media as the "Snowshoe Baby".

|

| |

|

"Art

was a remarkable man-a man of integrity

and character. Ralph Griffis, owner of the former

Chik Wauk Lodge on the south side of Saganaga Lake (now reclaimed

as part of the BWCAW) said after Art's death, 'Art was well

respected. I don't know of anyone who didn't like him.'"

|

| |

|

Art and Dinna hunted together, and Art ran a trap line until he was 94. He never retired, and throughout his 90's, everyone was amazed at how fit and active Art remained. At age 95, he cut many cords of wood, repaired roofs and worked

on the rebuilding of a 75-foot-long dock. He handled all the accounting

and paperwork for

the resort and had scheduled

and prepared the reservations

through the 2000 season. Up

until mid-March,

Art was speed walking two miles

a day around the harbor in Grand Marais, Minnesota, where he

had "wintered out."

"Canada has named a lake in the Quetico in his honor — Art Lake, which is located below Pickerel Lake and adjacent to Rawn Lake."

"The back cover reads, '…Quetico has had and

still has many home grown heroes. Chief Blackstone, Art Madsen…' [Quetico Provincial Park

- An Illustrated History.]"

Art was a remarkable man-a man

of integrity and character. Ralph Griffis, owner of the former

Chik Wauk Lodge on the south side of Saganaga Lake (now reclaimed

as part of the BWCAW) said after Art's death, "Art was well

respected. I don't know of anyone who didn't like him. I never

heard of him having any enemies."

In June, Shirley Peruniak, (retired Quetico's assistant naturalist/historian)

presented Art with a copy of her newly-published book,

Quetico Provincial Park

- An Illustrated History.

Her book contains many quotes and pictures of Art, along with his account of being caught out on the lake during the tragic winds of the July 4th, 1999, blow down. The back cover reads, "…Quetico has had and still has many home grown heroes. Chief Blackstone, Art Madsen…"

The Dawson Trail museum at French Lake, including many ranger stations throughout the Park offer albums, or transcribed and taped audio and video interviews of Art. Canada has named a lake in the Quetico in his honor-Art Lake, which is located below Pickerel Lake and adjacent

to Rawn Lake.

Helen Sue Manzo, Art Madsen's "Snowshoe Baby," is currently working on a book about Art's years as a Quetico Ranger.

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Ranger Art on

patrol

|

Dear Daddy

Dear Daddy

Do you remember bringing me

home, brand spanking new?

Over the frozen lake on a snowmachine we flew.

I remember hearing how you mended our pet Ka-Hootie

Who one day swooped and stole my bottle for booty.

Do you remember when I was only three?

Playing giddy-up, giddy-up on your knee.

I remember you standing strong and tall,

You'd lift me up to feel the soft deer on the wall.

Do you remember me running, and sobbing to you in the night?

Sudden, crashing thunder was the reason for my fright.

"Grumble, grumble, grumble," you'd imitate with

a stern face.

Giggling and reassured, I'd return to my resting place.

Do you remember when we'd plant brightly colored flowers?

Stopping to admire every creature, humming bird and bee.

I remember precious four-leaf clovers and a lunar cocoon!

Pleasant and lovely, warm breezes…summer over TOO soon!

Do you remember the chickadees you'd tamed?

Feeding from your hand, a picture to be framed.

I remember playing too long in the freezing cold,

You'd warm my hands and toes as a lecture I was told.

Do you remember after a tiresome day's guiding,

You planned swimming lessons that were always abiding.

I remember hooking the "funnest" fish,

I'd grimace, for to bring them in was my wish.

Do you remember after dinner we'd sit and talk long?

Teaching me to care for my health, keep God's laws and be

strong.

I remember when I was 16, sheets and a clothesline fell,

You encouraged me and assisted in rinsing all very well.

You taught me with gentleness,

wisdom and love.

Now, you continue to help me with my own.

Each day's example was how I was told.

This example…more to me than precious gold.

You are composed with honesty

and self-control,

Your tongue never brazen, haughty, foul, nor bold.

You're incredible, the BEST there could be,

Thank you for being my DADDY.

You're all the things a father

should be,

Ever busy days, but you had time for me.

You're an example of love,

And now, I better know my Father above.

Thank you for your example

of love…

For better I know my Father above.

Your girl,

Susie

Written by Helen Sue Manzo

Presented to Art Madsen on

his Ninetieth Birthday,

the Third of August, 1994

Note: Ka-Hootie was an orphaned,

Great Horned Owl;

the "funnest" fish to catch were bass

|

Art, age 93, and his daugher

Helen Sue "Susie"

Art, age 93, and his daugher

Helen Sue "Susie" |

|